What You Need To Know About Grafting Pecan Trees

Figure 2—An example of the progression of a topworked pecan tree. From left to right, top to bottom—(A) A pecan seedling on May 29, 2020. (B) Limbs removed and graftable limbs cut back. (C) Eleven pecan scions inlay bark grafted onto tree. (D) Three years of growth since grafting. Tree still needs to be pruned some before budbreak this spring.

Scion wood collection has been discussed in several past issues of Pecan South and other sources by several pecan scientists, including myself, so I will only provide a bulleted list below:

- Collect scion wood from trees that are free of disease, insect, and physical or winter damage.

- Choose young trees because they produce vigorous growth and are generally excellent scion wood sources.

- Cut the scion wood into 6, 12, or 18-inch sticks (usually limited by your storage bag size). If I have time, I prefer to seal the ends with wax or orange shellac, but many don’t seal the ends.

- Keep their basal ends together, and if you are cutting a lot of wood, then tie them in bundles of a known quantity (10, 25, or 50/bundle).

- Label them—recording the cultivar and date of collection, and do not mix varieties in the same bag.

- Place the scion wood in polyethylene bags with moist sphagnum peat moss, moist newspaper, or moist cedar shavings, and seal the bags. The packing material should be moist, not too wet, or your scion wood will mold.

- Store the sealed bags of scion wood in a standard refrigerator set at 34 to 42 degrees Fahrenheit until it is to be used later in the year.

- Never store scions in refrigerated units where fruits or vegetables are currently kept or have been stored recently. Stored fruits and vegetables release ethylene gas, which can cause woody plant buds to abort, making the scions useless.

- Keep the scions from freezing during storage. If you remove scion wood and see ice crystals in the bag, it is best to discard the entire bag.

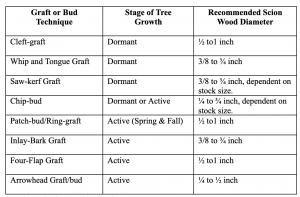

Now that we know how to collect scion wood, it’s time to discuss how to select the graft/bud technique you will be using over the dormant and active growing season. The size of your understock will often drive your decision on the grafting technique you select. Grafting techniques can be divided into two basic types. One is a graft joining a scion and understock of nearly equal size (whip grafting or four-flap grafting). And two is when you are attaching one or more small scions to a much larger understock (cleft, saw kerf, or bark grafting). When budding, the understock may be similar in size to the scion or larger than the scion wood.

Table 1—Grafts and bud techniques successfully used on pecan and the appropriate time to use them. (Chart & Photos by Charlie Graham)

Another factor in selecting a graft or budding technique is your past familiarity and success using that technique. I know a grower in Arkansas who has attempted whip grafting and patch budding on similar sized understocks. His success rate was poor on whip grafting but very good on patch budding. So when he needs to propagate a few pecan trees, I know he will use a patch bud because he has confidence in the procedure and has a history of success using it. But I encourage you to learn several grafting and budding techniques, although I know you will gravitate to a favorite over time. You never know when you will be forced to use a different propagation technique than your favorite.

Figure 1 shows some scion wood I received in the mail to propagate some hickory trees. I predominantly use inlay bark grafts and chip buds for the majority of trees I propagate, with an occasional four-flap. But in this case, I decided my best chance of success was to cleft graft the pencil-lead-sized scion onto pencil-sized understock. I had learned how to cleft graft decades ago but hadn’t used the technique in years. You will take a hit on your success percentage using material this small, but if it is all you have, you can make it work (I successfully grafted several trees in containers). I encourage you to learn several propagation techniques and practice them in your pecan orchard.

Figure 1—Small scion wood can still be grafted successfully using a cleft graft. (Photos by Charlie Graham)

Another factor that impacts your choice of propagation technique will be available time. We are lucky that there are many techniques that can be used to propagate pecan trees successfully. When you are a one-man operation, sometimes finding the time to graft or bud a tree can be a real challenge! Last year I was going to whip graft a few trees in March, which got postponed to inlaying some trees in late May/early June, but I wound up chip-budding trees in September and forcing them out in the following spring. Life happens, and sometimes your plans have to change. So, I reiterate. Learn several propagation techniques, not just one.

Most articles I have read over the past few years are generally aimed at grafting or budding young trees, typically less than 5 years old. But I want to wrap this article up by discussing 10-plus-year-old trees. The process of changing a large tree from one variety to an entirely different variety is called topworking. All sizes of trees can be topworked, but remember that older trees have many large branches making the task more difficult and maybe not worth your time. I have topworked 60-foot-tall trees, but it took over 30 grafts and two years to accomplish.

Topworking trees takes advantage of a well-established root system and brings the trees into production more quickly when compared to planting young trees. The initial step is to remove weak and poorly positioned limbs. This is best done in the dormant season when you can easily see the tree’s limb structure. Vigorous branches with a good crotch angle and well-spaced on the trunk are selected for grafting. You must picture in your mind the future framework and final tree form of each tree. Next, we should discuss “Why would you consider grafting a big pecan tree?”. Possible reasons for considering topworking include:

- Changing individual seedling trees or off variety trees included in your tree order so that they match the rest of the variety block. Let’s face it; we have all had trees that were labeled one variety, only to turn out to be another. Sometimes it is a rootstock seedling because the graft died, and sometimes it was a successfully grafted tree, but the wrong scion wood was used. Usually, we don’t find out until the trees start bearing nuts six to eight years later. At best, these off-trees are a nuisance, but they can be a starting point for disease and pest infestations that can spread to surrounding trees. We have the choice of sacrificing that percentage of production or topworking the trees over to the correct variety.

- Changing an unproductive variety to a new one with better production or disease resistance. This one can be tricky, as the new variety you select may turn out to be as bad as the one you are replacing. So, be sure your selected variety has been adequately tested in your location. Topworking a new variety into an orchard block allows you to redistribute the variety ‘make-up’ of the orchard by simultaneously decreasing trees of one variety while increasing the number of another. At Noble Research Insitute, we are currently transitioning an orchard that was predominantly ‘Pawnee’ with ‘Kanza’ as a pollinator to an orchard that is predominantly ‘Kanza,’ which has much better disease resistance.

- Accelerating initiation of production of a new variety. Grafts on topworked trees grow and become productive faster than newly planted trees because grafted trees have the force of an established mature root system behind them, while newly planted trees do not. Furthermore, you eliminate the time needed to remove old trees, re-level the land, and re-plant new trees.

- Testing new varieties in an existing orchard. It is important to test a new variety in your local conditions before grafting or planting a large block of trees. Topworking several trees can provide a quick, efficient way to look at several new varieties. The test area can be an outside row so that it won’t interfere with normal management and harvesting operations.

- Correcting a pollination issue in an orchard. It is not uncommon to find some older pecan orchards that were planted in solid 10-to-20-acre blocks of a single variety. Dr. Bruce Wood, retired USDA Scientist, determined that these blocks often suffer from excessive premature nut drop due to selfing and decreased production compared to mixed variety blocks of trees with good cross-pollination. Production and nut quality can be improved by topworking selected trees in the orchard with a pecan variety that provides complimentary cross-pollination.

- Expanding the number of varieties when you are limited by tree number. This is a common necessity when a homeowner only has one or two trees in their yard. Pecans need to be cross-pollinated, and sometimes the only way to accomplish that is by putting more than one variety into an existing tree. I had one homeowner that had a single tree in their yard with nine limbs available for grafting (after limb thinning). So they had me graft a different pecan variety on each limb. Five protogynous and four protandrous, so there was good cross-pollination.

While grafts can fail for several reasons, the primary causes are usually poor cambial contact and desiccation of the scion. You must have “intimate cambial contact” for the graft to stand a chance, and it must not dry out before it can start growing. All types of products are used to prevent desiccation—grafting wax, ‘Tree-kote’ type wound dressings, plastic bags, duct tape, electric tape, grafting tape, parafilm, orange shellac, and glue. No matter which you choose, you must seal the wood well enough to prevent desiccation from occurring before a callus has time to form. Other reasons for graft failure include:

- Stock and scion were not compatible.

- Scion was grafted upside down (yes, this does happen).

- Grafting was done at the wrong time of season.

- Scion or understock was weak or unhealthy.

- Scion wood dried out before or during storage.

- Scion wood froze in storage.

- Scions were not collected in full dormancy and forced out too soon after grafting.

- The scion was physically displaced by birds, wind, or other means.

- The graft was shaded out by excessive sucker growth.

- The graft was attacked by insects (bud moth) or diseases.

- The scion was girdled because the tape was not loosened or removed in time.

If I have an occasional graft or bud fail to take, I seldom give it a second thought as to why. But if you have a massive failure, you need to do some investigative work to figure out what went wrong. Topworking trees takes a good deal of time, so you don’t want to spend days grafting only to find out your scion wood froze in storage and all that time was wasted.