Market timing your pecan production? A questionable decision.

Can I “time the pecan market” and take a year off from pecan growing during a bad market?

Pecan nut clusters weigh down the trees in Tommy Taylor's orchard. (Photo by Blair Krebs)

His questions surrounded the impact on pecan production next year in 2022 and beyond if management inputs are withheld in the current season. Let me answer the question by saying that attempting to grow pecans only in those years when the market is favorable works about as well as a horticulturist buying tech stocks. Let’s discuss the unique things about pecan trees that make it uniquely challenging to be a “day-trading pecan grower.”

Crop Predictors

Most people know that pecan is an alternate-bearing fruit tree. Heavy fruiting years, aka “on years,” are succeeded by lighter fruiting years, called “off years.” Two general theories exist as to why pecans have this biennial pattern.

The carbohydrate theory attempts to explain it as a failure of pecan trees to build up and store the carbohydrates needed to do two jobs: form, grow, and finish a fruit crop being grown in the current season and prepare itself to differentiate new pistillate/female flower buds in the following season. This theory has been challenged by the very existence of the ‘Pawnee’ variety. ‘Pawnee’ completes its fruit production by late August in some locations and then has perhaps 60 to 80 additional days to build carbohydrates for the following year. ‘Pawnee’ is as distinctly alternate bearing as any that we grow, despite having this lengthy, end-of-the-season rest period.

The phytohormone theory attempts to explain alternate bearing by stating that there is a hormonal flower bud induction step happening during the kernel development stage (in August) that is dependent on hormone availability during the summer formation of buds on pecan stems. If a pecan tree is carrying too heavy a crop, the hormones are either depleted or over-produced, and many buds will not differentiate pistillate flowers the following spring. This theory has been challenged by hormone treatments failing to eliminate alternate bearing and by the fact that pistillate flowers, unlike male catkins, simply don’t arise within buds until just before budbreak in the spring.

Although we don’t know the exact mechanistic steps for pecan alternate bearing, we have learned ways to manipulate it somewhat. Crop-thinning—using a mechanical trunk shaker to reduce the nut crop load on a pecan tree in July—is very effective at bringing back production in the following crop year. We’ve well-demonstrated an ability to, in fact, have trees side by side in an orchard—one with a crop and the other without in alternating years by shaking all of the nuts off a heavily cropped tree in late July or early August.

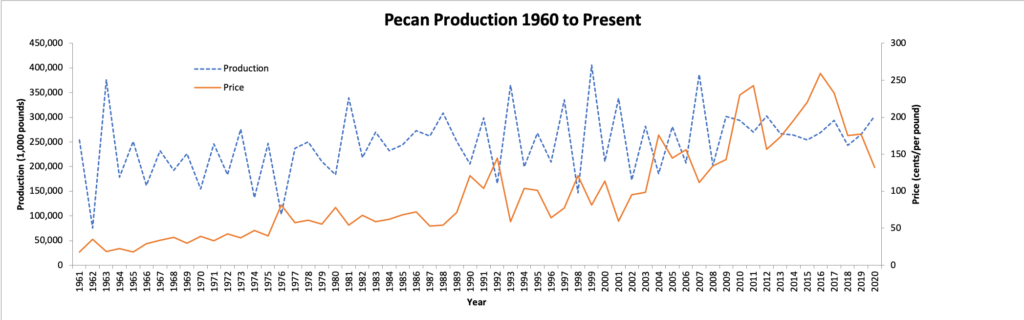

Figure 1: The U.S. pecan production and average price per pound from 1961 to 2020. Data gathered from USDA-NASS Pecan Production reports. (Chart by Blair Krebs, Pecan South)

Additional experiences, like heavy pecan nut casebearer attacks, hailstorms, and hurricanes that cause June to August-timed crop loss, have taught us that the biggest predictor of next year’s pecan crop (assuming otherwise good tree health) is this year’s pecan crop. Figure 1 depicts this general effect on the whole of the U.S. pecan crop over time. Lower crops follow high crops in all but a couple of instances.

This two-year relationship that is really a perpetual relationship of one pecan crop affecting another makes the forfeiting or sacrificing of the 2021 pecan crop impactful on the 2022 crop, which then affects the 2023 crop and so on. Either an orchard has to be clearly “off” in the current year from natural causes, setting up the possibility of better production next year, or a grower has to take steps to eliminate the crop to favorably influence the possibility for a crop next year.

Eliminate a pecan crop? That’s hard for many people to do—even eliminating part of their current pecan crop through July trunk shaking is a hard pill to swallow. An orchard manager must be willing to assume the risk that potential crop pitfalls next year won’t be overcome successfully one year forward and that better prices will also manifest in, say, 18 months to two years!

While eliminating or reducing a pecan crop actively by shaking it off or passively through withholding insect control might manage the most important predictor of next year’s pecan crop, it does not deal with the second most important predictor—pecan foliage. Regardless of the alternate bearing theory, pecan foliage is the source for carbohydrate and phytohormone production. Not only are the leaves critical to manufacturing all the resources for a pecan crop, but they also keep next year’s leaf crop in a dormant state.

“Keep the leaves on the trees until frost” is a long-held recommendation for managing alternate bearing in pecan orchards. It’s based on research done by the late Dr. Ray Worley in Georgia that demonstrated better return bloom in pecan trees that kept their leaves until early November versus September or October. Worley did his study with ‘Farley,’ a late shuck-split pecan variety that didn’t mature until late October. Hurricanes—especially those that crash through pecan orchards after shell hardening and take most of the leaf crop—usually cause significant budbreak and re-leafing. When a new leaf crop forms late, experience has shown that return bloom on those trees may be little to none.

Leaf Life

Trees will form approximately 90 percent of the leaves needed for perennial pecan cropping in the first six weeks of the growing season. These leaves need to survive and thrive for at least 200 days. The magnitude of this statement implies that taking a complete year off from managing a pecan orchard is dangerous.

For the humid southeastern pecan growing region, three major leaf diseases must be prevented: Pecan scab, leaf die-back (caused by Neofusicoccum caryigenum), and downy spot. All of these have the potential to impact more western regions, including Central Texas, in above-average rainfall years. Failure to treat leaves with fungicides from budbreak to pollination may result in heavy leaf losses that start in July and devastate orchards by late August. Minor fungal diseases, like zonate leaf spot, liver spot, and others, can add to the burden of foliage condition as the season progresses.

According to retired Extension Entomologist Bill Ree, there are 103 different known insects that feed on pecan leaves. Some make rare appearances and many of them are minor, but a few are as equally devastating to pecan foliage health as the fungi described above, including black pecan aphid, pecan leaf scorch mite, and pecan phylloxera. Phylloxera is an early-season problem, while black aphids and mites catch growers by surprise who are not scouting properly in August and September. We can also add everything from the yellow aphid complex to fall webworms, June beetles, and blotch leaf miners as reasons to not walk away from a pecan orchard over the course of one growing season.

Pecan leaves will be larger and healthier when they receive adequate amounts of zinc early in the growing season. Every grower in the U.S., except those with acid soils and a soil-fertilization program that includes zinc, should make foliar applications of zinc sulfate or zinc nitrate in the early part of the growing season for best foliage health. Another micronutrient of importance in pecan orchards is nickel, with research supporting two sprays per year to combat mouse-ear disorder, improve scab control, and reduce June drop of nuts and water-stage split.

A comprehensive spray program that promotes healthy pecan foliage formation and retention through disease prevention, insect control, and micronutrient supplementation is an important factor for producing a pecan nut crop in the current season. It is equally important to irrigate, fertilize, and manage crop load to optimize pecan nut yield and quality.

For pecan growers looking past the current season to 2022 and beyond, the spray program is the most important factor for keeping future crop potential viable. You can withhold or reduce water and fertilizer in the current season and still make a crop next year if you keep foliage healthy. In contrast, you can fertilize and water all you want this year, and you may not make a crop at all next year if the foliage is not protected with a spray program.

I will concede that a spray program for growers facing no crop or wanting no crop this year can be abbreviated or limited compared to what should happen when a nut crop is in play. Three fungicide sprays early that include FRAC Group 3, Group 11, and Group 33 with zinc and nickel is a cost-conservative program that sets up foliage to endure through most of the season. Scouting must also be done to keep insects and late-season minor fungal diseases from breaking down overall pecan foliage health and condition.

Crowd Control

When pecan prices are weak, the penalty for sub-par yield and poor nut quality is magnified. Growers that can produce good quality pecans year-in and year-out will outperform the market average over time because there is an abundance of pecan orchards across the industry that are old in age and crowded. In a strong price market year, these orchards consistently receive less for their pecans, and in a weak market year, they sometimes can’t even sell their crop. Growers across the Pecan Belt, especially in the Southeast where more orchards are thinned rather than hedged, need to critically evaluate orchard crowding and sunlight availability during this time of market volatility.

Grower discouragement with prices naturally tends to lead to a fallback in recommended management practices, like pruning and tree removal or irrigation system upgrades. I get it. You’re being paid less for your crop, so the reaction tends to be “spend less” or “let’s get by another year without taking out trees.” Cash flow becomes a problem, and conservatism is the reaction. It needs to be the opposite!

Pecan orchards are a long-term agricultural endeavor, but the economics are only good over the long term if production and quality potential are maintained. Pecan orchards either have to be hedged, beginning in about Year 14 on a 30-foot spacing, or a series of tree removals have to be made when sunlight levels decline. We have used 50 percent sunlight on the orchard floor as a crowding benchmark recommendation. I’m beginning to believe it’s too subjective, and growers fail to evaluate and act on it the way they should.

Perhaps a better approach is to go back to the old approach of measuring cross-sectional trunk area (CSTA). Measure trunk diameters at breast height on an acre of trees and calculate square feet of CSTA per acre (using the formula for area of a circle and converting units to feet). In the Southeast, the limit should be 25 to 30 feet CSTA per acre. Above that, growers should remove trees to keep the sunlight at a level conducive to better yield, nut size, and kernel percentage.

I maintain that a grower with no crop or who doesn’t want to harvest because of expected low prices should critically evaluate their orchard and either rent a hedger or put some trees on the ground now. The infusion of sunlight will enhance foliage health this year, translating to better yield and quality potential on the remaining trees for the next year and beyond.

Crystal Ball

My good friend in Alabama, Gary Underwood, was always asking me, “So what does your crystal ball tell you we’re going to have this year?”

It would sure help those of us in Extension and Research to have a crystal ball to predict the coming pecan crop, wholesale prices, and whether or not a hurricane is in the works. From the print date of this article, there are 120 to 150 days ahead this season for many factors to come into play and influence the size of the U.S. pecan crop, the quality, and the prices offered.

One way or another, I know one thing for sure: somebody with a pecan orchard somewhere is going to produce an excellent crop, and they are going to get a decent price for their nuts; maybe not $6.00 or even $5.00 a point, but a price respectable and reflective of what good managers who keep plugging away at growing pecans year in and year out get