Protecting Our Crop, Protecting Our Fungicides

With careful planning and action, you can protect your crop and prevent fungicide resistance in scab and other fungal diseases.

Just to be sure we are talking about the same fungus, pecan scab scientifically is currently known as Venturia effusa but has been called many other names, including Fusicladium effusum, Fusicladosporium effusum, Fusicladium caryigenum, Cladosporium caryigenum, and Cladosporium effusum. Pathologists seem to have a hard time deciding just how to classify this fungus, but I think it is getting close to being in its proper place. For this discussion, we will just stick to calling it pecan scab.

Pecan scab is by far the most economically significant disease that infects pecans in the southeastern United States and is the focal point in developing a fungicide spray program. But it is not the only disease that growers may face in the new season. I’m sure I will receive questions on many other diseases, including Downy Leaf Spot, Gnomonia Leaf Spot, Brown Leaf Spot, Anthracnose, Powdery Mildew, and Neofusicoccum. We’ll begin to confront these diseases in the coming months, so now is a good time to review fungicide classification and look at how this classification influences your fungicide scheduling throughout the year.

Let’s start with the basics. You can select a fungicide schedule from any state you want, but all of the programs will probably talk about fungicide resistance and rotating chemical groups or FRAC codes when you spray.

Healthy pecan foliage is the cornerstone to a successful year. Knowing when and what to spray can help growers achieve that success.

What is a FRAC code? The FRAC code was developed by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), which is a specialist technical group of CropLife International. This group “provide[s] fungicide resistance management guidelines to prolong the effectiveness of ‘at risk’ fungicides and to limit crop losses.” The FRAC code or group is a letter or number combination assigned by FRAC to categorize the active ingredients of chemical products that have the potential for cross-resistance. What this means is that two chemicals with the same FRAC code have the same target site; so, if a fungus becomes resistant to one chemical, it is probably resistant to the other. For instance, Orbit (propiconazole) and Enable (fenbuconazole) are both FRAC Code 3 DMI fungicides. If scab develops resistance to Orbit, then there is a high likelihood that it is immune to Enable, even if you have never sprayed the second chemical.

While we are on this topic, we should clarify the difference between the target site and mode of action (MOA) of pesticides, as these two are often incorrectly used as interchangeable phrases. A fungicide’s mode of action is the specific biochemical pathway affected in the pathogen, such as cell wall synthesis. A fungicide has a particular target site in a fungus that is the exact location where the fungicide inhibits an action or activity within the fungus. An example of a target site might be interfering with the activity of a particular enzyme or metabolic process. So, two different chemicals such as Abound (azoxystrobin) and Luna Privilege (fluopyram) can have the same mode of action (inhibit fungal respiration) but sit in different FRAC groups because they target a different part of the respiratory system. Abound (Group 11) targets cytochrome bc1, while Luna Privilege (Group 7) targets succinate-dehydrogenase. This jargon may all seem a bit confusing, so why is it important?

Fungicides are the primary method to manage pecan scab on susceptible cultivars. In the United States, there are currently eight FRAC groups of fungicides that are typically used in pecan orchards to control diseases. These groups include:

- Group 1 – MBC fungicides, MOA – cytoskeleton and motor protein, high risk for resistance. Examples: Helena T-Methyl 4.5 Ag, Incognito 4.5F, Nufarm T-Methyl 4.5F, Topsin M WSB.

- Group 3 – DMI fungicides, MOA – sterol biosynthesis in membranes, medium risk for resistance. Examples: Bumper 41.8EC, Enable 2F, Folicur 3.6F, Orbit, Quash,

- Group 7 – SDHI fungicides, MOA – respiration inhibition, medium to high risk for resistance. Examples: Luna Privilege, Endura

- Group 11 – QoI fungicides, MOA – respiration inhibition, high risk for resistance. Examples: Abound, Headline, Insignia, Luna Sensation, Sovran

- Group 30 – Organo tin fungicides, MOA – respiration inhibition, low to medium risk for resistance. Examples: Agri Tin Flowable, Super Tin 4L

- Group M3 – Dithiocarbamates, MOA – multi-site, low risk for resistance. Example: Ziram 76DF

- Group P7 – Phosphonates, MOA – host plant defense induction, low risk for resistance. Examples: Agrifos, Fosphite, FungiPhite, Kphite 7LP, Phostrol, ProPhyt, Rampart

- Group U12 – Guanidines, MOA – unknown, low to medium risk for resistance. Example: Elast 400F.

As we begin a new pecan season, healthy pecan foliage is the cornerstone to a successful year. Knowing when and what to spray can help growers achieve that success. The pecan scab fungus overwinters on canopy stems and branches, old shucks, and leaf debris. These overwintering sites serve as the primary source of inoculum and lead to early pecan scab infections on the foliage. These early-season foliar lesions then serve as an important source of inoculum for later season infection of the nuts. Additionally, many of the other diseases I mentioned earlier can lead to reduced photosynthesis and early defoliation, thereby affecting not only this year’s crop but next year’s as well.

Systemic (translaminar, xylem mobile) fungicides such as Groups 1, 3, 7, and 11 are typically used early in the season in most spray schedules; in contrast, protectant fungicides in Groups 30 and U12 are generally used as cover sprays later in the schedule. The best times to use Groups M3 and P7 (formally 33) are still being determined. However, the timing of fungicide use cannot be determined strictly on its ability to control scab and mobility.

To design a long-term spray schedule, we must also factor in disease resistance management. Groups 1, 3, 7, and 11 have a medium to high chance of developing resistance, so growers should avoid late-season applications. Producers should instead use these groups in pre-pollination sprays and early cover sprays. Because Groups 30, M3, P7, and U12 have a lower risk of developing resistance, the use of these chemicals later in the spray schedule would be beneficial for resistance management in a pecan orchard. The primary goal of resistance management is to delay the development of resistant fungal strains, not to manage existing resistant populations. Therefore, the grower wants to minimize the use of high-risk fungicides without sacrificing disease control. Remember that consecutive applications or too many applications of the same fungicide group in a growing season may exacerbate pathogen resistance.

To ensure prolonged efficacy against pecan scab, steps in a good resistance program would include:

Start spray programs early: Spray programs that begin before pathogens attack keep fungal populations low and reduce the likelihood of a resistant population developing in the orchard. Most Extension recommendations call for fungicide sprays to start no later than the “parachute” stage, sometimes called “leaf burst.” Infections established early in the season tend to be more severe and result in the greatest crop loss later in the season. Fungicide applications should be made prior to a rainfall event, not after infection has occurred.

Alternate products and restrict the applications of high-risk fungicides: Use spray programs that alternate products from different fungicide groups. Do not consecutively spray one fungicide or fungicides in the same group. Group numbers can generally be found on the first page at the top right corner of product labels. Reduce the number of high-risk fungicides to only one or two applications per year.

Use at least the minimum-labeled rate and do not extend spray intervals beyond label specifications: Avoid using fungicides at rates below the minimum-labeled rate. While this choice might save you a little money in the short term, it can shorten the useful life of a fungicide. Additionally, lengthening fungicide application intervals excessively may leave a crop unprotected, providing the pathogen population the opportunity to multiply, and increasing the likelihood for a resistant population to develop. Also, poor spray coverage is a concern because low doses of fungicides may accelerate the selection for resistant strains of V. effusa.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM): Fungicide applications should be integrated into an overall disease and pest management program. Cultural practices known to reduce disease development should be followed. Plant disease-resistant pecan varieties, or if using susceptible varieties, avoid planting them in wet, low lying areas in the orchard. When establishing new orchards, tree spacing and orientation are important considerations because adequate exposure to sunlight and good airflow are two keys to keeping foliage dry. Keeping orchard groundcover mowed and low limbs pruned will increase airflow and reduce wet foliage’s drying time. Selective pruning of damaged branches during the dormant season is also recommended to promote sun exposure and air circulation. Finally, good sanitation practices are recommended to limit the amount of primary inoculum that may cause infection. Ensuring old shucks (husks) and leaves are removed from trees and the orchard floor after harvest can also reduce sources of primary inoculum. This removal can be accomplished by flail mowing or burning. Additionally, research suggests that the use of dodine or lime sulfur as a late dormancy spray may reduce sporulation in overwintering scab lesions; still, more research is needed on other labeled fungicides.

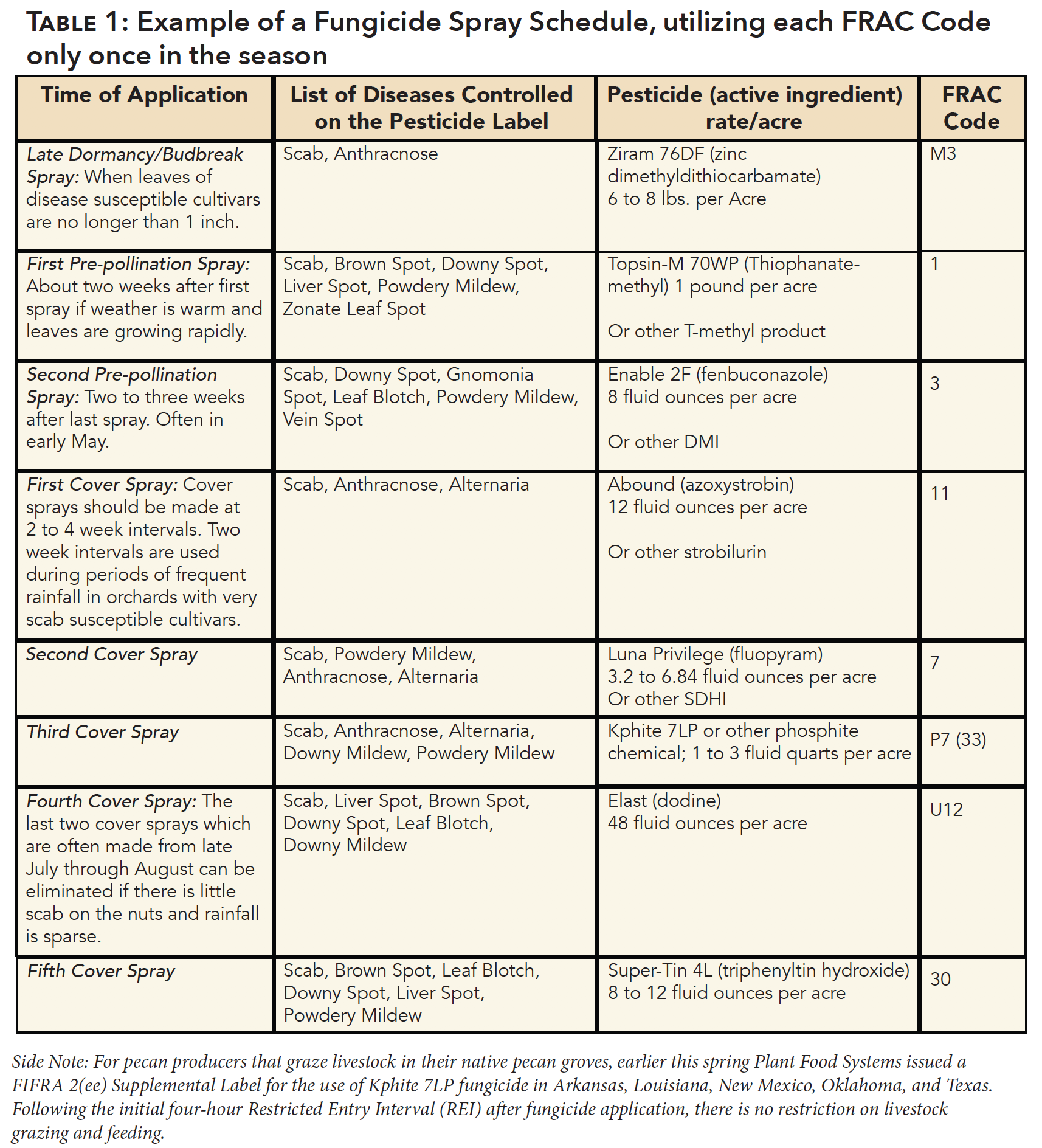

Many pecan varieties with moderate scab resistance can be managed with only six to eight fungicide sprays per year in many locations across the Pecan Belt. So, what would a spray schedule look like if it was designed to only use each FRAC group once during the pecan season? Is that even possible? Table 1, at the top of the page, shows an example of such a spray program. Schedules like this one are definitely a worthy target to aim for in a fungicide resistance program.