Pecans in Mexico

An Overview of the Mexican Pecan Industry

A high-density pecan orchard in Caborca, Sonora, Mexico. (Photos courtesy of Robert Hatch)

Pecans originated in northern Mexico and the southeastern part of the USA. Although walnuts and other nuts have been consumed and marketed worldwide for centuries, pecans were hand harvested and traded first by Native Americans in the river valleys of Texas for hundreds of years. Only now, more and more countries are becoming acquainted with pecans.

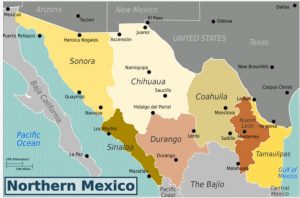

In the last three years, most (60%) of Mexico’s pecans were grown in the border state of Chihuahua, and another 15% in each of two other northern states, the state of Coahuila and Sonora. Each state faces the same challenge—lack of water. On the coastal plain of Hermosillo, Sonora, water is pumped from the aquifer, which is barely maintaining its level by strict adherence to pumping quotas. In Chihuahua, many wells have been drilled, and water levels continue to drop.

Growers in the southeastern part of the United States, where there is high humidity and rain, repeatedly spray for scab. A friend in Georgia recently remarked that “spraying for scab is a challenge, but at least we have plenty of water.”

The predominant variety is ‘Western Schley’ in Chihuahua and ‘Wichita’ in Sonora. The latter is a large nut preferred by Chinese consumers. Sonora exports a significant volume of Wichita to China.

Many new plantings are high density, with trees established as close as 15 by 30 feet (5 by 10 meters), with up to 80 trees per acre (200 per hectare). Due to more trees per acre, these plantings come into bearing earlier than those with fewer trees and improve the return on investment. Hedging of closely planted trees begins in the first ten years.

A significant challenge in Sonora is the lack of sufficient chilling hours. Pecans require over 500 chilling hours (under 45 degrees Fahrenheit in winter). Since the Hermosillo area has fewer than 500 chilling hours (between 150 and 350), growers and their technicians have learned ways to confront this dilemma.

Another challenge for growing pecans in Hermosillo, Sonora, is early nut germination, or vivipary. A significant percentage of the crop germinates in some years, causing losses of 25% or more. Growers avoid some of these problems by harvesting pecans early when the foliage and the early shuck opening is still green.

In Hermosillo, warm weather during bloom, 95 degrees F (35°C), especially with the wind, causes fruit abortion. High temperatures during nut maturation also increase vivipary. Producers in Hermosillo have recently started spraying pecan trees with kaolin clay sprays to protect the canopy in hot and dry conditions; these sprays have helped diminish some of the adverse effects of heat stress. Some Hermosillo growers also install a “dual” irrigation system; they use drip irrigation for water savings and micro-sprinklers during bloom to lower ambient temperature and increase humidity.

Pecan harvest in Chihuahua is done with conventional equipment, much like in the United States. In Hermosillo, workers harvest pecan trees early and gather most of the nuts by hand. The reason growers use hand labor is to maintain their workforce. After pecans are harvested, field labor is used to harvest citrus, prune table grapes, work with vegetables, and conduct other agricultural practices.

Large nurseries in Montemorelos, near Monterrey, Mexico, supply “balled,” not bare-root trees. Nursery trees are dug with a long spade-like shovel. The heavy clay soil in the nurseries remains attached to the roots, and the soil ball is then wrapped with plastic. It would be difficult to dig the trees with equipment, as practiced in the U.S. because the soil adheres to the root system. One advantage of “balled” trees is not exposing roots to air where they dry. When done correctly, the mortality of “balled” nursery trees is less than 2%.

One new development in growing pecans in Mexico is an effort to analyze and monitor reserves in tree roots. In the fall, small portions of the roots are sent to labs to determine their reserves. With this data, growers are better informed on managing pruning, applying nutrients, and making decisions to avoid alternate bearing.

Growers in Mexico are fortunate to have available resources such as competent technicians, good labor, and finances. The larger growers— some of whom own up to 3,000 acres (1,200 hectares)— have modern farm equipment, irrigation systems, and processing plants.

Most of our technicians have college degrees, including some PhDs. For several years, I taught Horticulture at the University of Sonora in Hermosillo. Some of my students have become experts in pecans; for example, Dr. Humberto Nuñez (research specialist at the government experiment station, INIFAP, in Hermosillo and a graduate of the University of Arizona) and Edgardo Urias (one of the top pecan technicians in Mexico). Other specialists in Mexico include Victor Esparza (MS from New Mexico State University), Dr. Jose Alfredo Samaniego (INIFAP in Matamoros, Coahuila), and Dr. Hector Tarango, a researcher in Chihuahua who has published articles about growing pecans.

Additionally, Mexican pecan growers and industry members from around the world gather each year for annual pecan conferences in Chihuahua and Hermosillo. All are welcome. One can register and attend these conferences with the following links: “el Día de Nogalero” in Chihuahua and “Simposio Internacional de Nogal Pecanero” in Hermosillo.

As consumers worldwide become familiar with pecans, demand will hopefully increase to consume additional volume from newly planted acres primarily in the United States and Mexico.