The Leafminers of Pecan

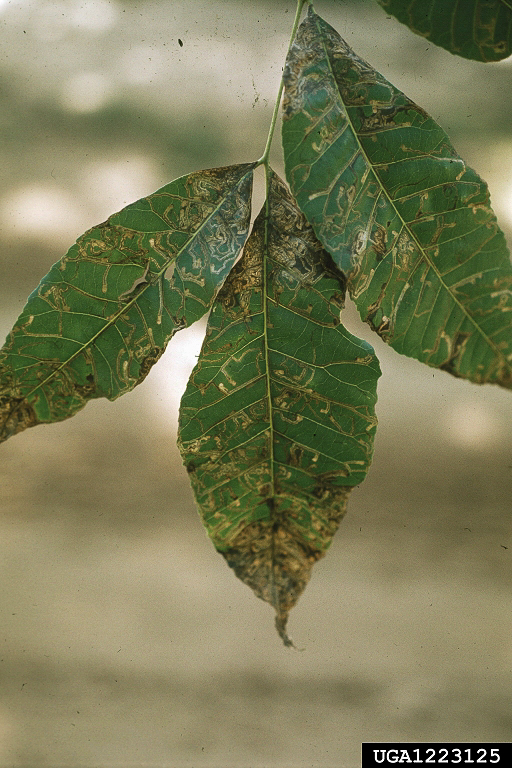

This image shows the severity of leaf damage during an outbreak of the pecan serpentine leafminer. (Photo by Dr. Jerry Payne; USDA)

The leafminers discussed here all belong in the Order of insects containing the moths and butterflies, i.e., the Lepidoptera. It should be noted that there are also some species of flies (Diptera), beetles (Coleoptera), and wasps (Hymenoptera) that are leafminers—but not on pecan. If there is a resource to be exploited, there will generally be several species trying to do just that, as evidenced by the four leafminer species feeding on pecan foliage.

The leafminers of pecan are generally minor pests causing negligible damage unless they reach outbreak populations. When such populations are reached, leaf damage can be substantial. Factors leading to outbreak populations are not exactly known. In some cases, the application of broad-spectrum insecticides likely wipes out the leafminers’ natural enemies—parasitic wasps—allowing the leafminer populations to flare by outpacing the return growth and development of the killed-off parasitic wasps. In some cases, outbreaks of leafminers are not associated with any known insecticide application. Environmental constraints likely led to favorable conditions for leafminers allowing them to flourish. Luckily for us, a leafminer outbreak this year does not build up a population that leads to a guaranteed outbreak next year.

As concerns the biology of leafminers, they have four distinct life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult—same as all the other moth species in this Order of insects. Payne et al. (1971) stated that the pecan serpentine leafminer lays eggs on the upper surface of the pecan leaf. The resulting larvae hatch by eating through the bottom of the egg, going directly into the leaf. It is not reported if the other three species have similar egg-laying habits. In fact, very little is reported on the bionomics of the leafminers attacking pecan. These larvae ‘mine’ the leaf, staying within it and leaving visible evidence of where feeding has occurred.

Payne et al. (1974) documented the characteristics of mines made by each of the four species attacking pecan, thus allowing quick identification of the species in question. After feeding within the pecan leaf, the mature serpentine leafminer larva leaves the leaf to pupate in cocoons attached to debris on the ground. Adults emerge from cocoons in about a week during the growing season, but it is the pupal stage that overwinters. For the pecan serpentine leafminers, there are four generations each season, from June to early November, across the southeastern United States.

As its name implies, the pecan serpentine leafminer (S. juglandifoliella) leaves behind narrow mines within the leaf that can wind around and may follow leaf veins and the midrib but generally avoids crossing over them. In contrast, feeding by the upper surface blotch leafminer (C. caryaefoliella) leaves irregularly shaped mines that look like, as suspected, blotches on the upper surface of leaves. This blotch is visible when the upper surface of the leaf is viewed but generally not when the lower surface is viewed. The blotches often appear as light or dark brown blisters on the upper surface of the leaves. This leafminer pupates within the blotch, and oftentimes, the pupal case can be seen protruding from the leaf.

And of course, if we have an upper surface blotch leafminer, you can be sure we have a lower surface blotch leafminer (C. caryaealbella). The blotches formed by this insect are irregular and will be found on the lower leaf surface (although the upper leaf surface may be discolored right above the damage).

The last leafminer, C. lucifluella, also creates transparent blotch mines; however, these mines are visible on both the lower and upper leaf surfaces. Leaf blotches infested with C. lucifluella will eventually leave a hole through the leaf as if a hole punch had been used. The hole in the leaf is formed by the larva when it chews through the upper and lower leaf surfaces to create a case in which the larva will pupate. This leaf case, which is free from the leaf, may even be carried by the larva away from the blotch where it was cut to be fastened with silk onto a leaf or twig.

Several species of parasitic wasps attack the leafminers and generally keep them in check. I was once told that an almost sure way to flare leafminers was to use an insect growth regulator (IGR). The IGRs can be quite detrimental to natural enemies, and this was the likely mechanism for how IGRs were said to flare leafminers. With this in mind, remember that the level of natural control taking place in your orchards is higher than you will ever know. However, there is a definite need for pest management when economic thresholds are exceeded, and there are numerous efficacious products for almost all situations.

When leafminer control is warranted, the insecticidal chemistries that are efficacious against pecan nut casebearer, hickory shuckworm, and pecan budmoth will also be efficacious against the leafminers. Previous research showed that sampling leaves to determine when leafminers begin to pupate was successful at forecasting when adult leafminers would emerge and a single application of an efficacious insecticide would control the next generation of leafminers (Heyerdahl and Dutcher 1985).

Four species of leafminers attack pecan foliage. Characteristic feeding patterns on pecan foliage allow for the identification of each species. Outbreaks of leafminers on pecan tend to be rare but can occur. If control is needed, efficacious insecticidal chemistries for use against pecan nut casebearer, hickory shuckworm, and pecan budmoth will also control leafminers.