Cover Crops—Cover up out there!

How can cover crops help your pecan orchard? Here are the pros and cons.

50-year-old pecan trees with a cover crop. (Photo from FICO)

I realize of course there are diverse production systems with different management strategies and some favor the addition of cover crops, while some don’t. Especially important is the bigger differences in climate across the regions. But I often wonder too if just the thought of adding another crop to the operation is simply too overwhelming for some growers, as cover crops create both an added expense and an added element to manage in one’s operation.

My first introduction to this method was back in a graduate-level class. I first utilized the method in my own rotation of crops grown in the vegetable garden beds in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and now I use them here in Arizona. These are not raised beds where a soil-less medium might be used. These are garden beds directly implemented into the native soil. My personal observations from using cover crops in this backyard setting are reduced pressure of undesirable insects, increased soil organic matter, and reduced fertilizer use. But I recently attended a webinar that focused on the returns in adding cover crops to western agriculture production to care for the soil, cover the orchard floor, and capture more carbon—not release it.

In the western arid region, no matter the production system (e.g., pistachio, grape, vegetable), the returns on soil improvement alone are actually pretty darn good. We should be taking a closer look at incorporating cover crops in the West’s vast pecan production, not disregarding it anymore as something unattainable. It is!

Cover Crop 101

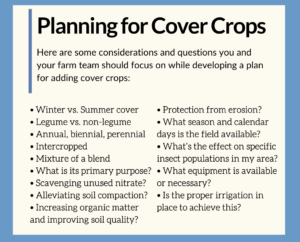

So, what does a cover crop mean to you? Do you think of it in terms of an alternative crop, maybe an intercrop, or a double crop? For this article, let’s think of it just as it’s named: a cover. A cover crop is defined as a secondary crop that replaces bare, fallow ground, often not harvested, and not a cash crop, but offers benefits to the cash crop harvested.

There are other definitions used, as well. According to the Summer Cover Crop Use in Arizona Vegetable Production Systems from University of Arizona Extension Publication, a cash crop is “a crop grown with a major cash crop (or during the off-season of the cash crop) as a major source for sustaining and increasing agricultural productivity.” The Western Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SARE) defines it as “a crop used primarily to slow erosion, improve soil health, enhance water availability, smother weeds, help control pests and diseases, increase biodiversity and bring a host of other benefits to your farm. Cover crops help when it doesn’t rain, they help when it rains, and they help when it pours” (Cover Crops for Sustainable Crop Rotations, 2015, Western SARE, online).

Another excellent definition and list of benefits can be found with the USDA Natural Resources and Conservation Services (NRCS). It’s a pretty lengthy definition, so I have left it out of this article for the sake of space here.

Cover crops are not a new idea either, as you probably know. Even though its concept and use have been increasing over the last four decades, cover crop use is actually pretty ancient, evolving from the concept of “green manure,” which is grown to incorporate into and improve the soil. Usually, cover crops are not incorporated into the soil as in the use of tilling or discing them under in perennial cropping systems. Mostly they are mowed, and the biomass is left to decompose.

Some of the oldest civilizations in the world, including China and Rome, referenced cover crops. That’s right! It’s wisdom known to the ancients, the first of the land stewards. The Georgics, authored by a Roman poet simply called Virgil, is an example of when the concept was first documented between 70 and 19 BCE. He authored several volumes, and in some of the work, he spoke of using alfalfa, clovers, and lupine for increased wheat yields.

In the late 1700s, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington also documented the use of grasses and legumes in rotation with tobacco, wheat, and corn. They made mention of its use for restoring depleted land and to reduce emigration and starvation. Cover crop use really was not widely adopted until the 1860s.

Within the past few decades, the federal government has really been encouraging the use of cover crops in all forms of agricultural production, even in cattle production. If you wonder why as a land steward, this fact may interest you. It is due to the fact that agriculture is the number one contributor of nonpoint source pollution to U.S. waterways. Of course, urbanization, homeowners, and industry also contribute to this pollution. If you want to see the effects of nitrogen and phosphorus leaching, I encourage you to perform an internet search using the terms “dead zone Gulf of Mexico or Chesapeake Bay.” The heavy push for cover crop use is to help reduce the leaching of nutrients from agricultural land into waterways.

I know what a great burden this brings to agricultural land stewards, especially given that we have more and more people to feed and sustain. As an educator, I see the burden. I also see that farmers constantly have to face new norms, which means farmers have to re-evaluate their land management systems and management plans. But cover crops will ultimately help farms from losing those rich nutrients into the depths of the soil. What are some other uses though?

Cover Crops’ Uses and Benefits

In a recent study supported by Western SARE, most western production farms were motivated to use cover crops to control soil erosion and increase soil health. Other uses mentioned were to reduce soil compaction and weed pressure, to supplement grazing and forage production, or to cycle nutrients (so as not to lose nutrients during the off-season), as mentioned above. More uses of cover crops are for water quality, soil organic matter, and control of disease, nematode, and insect pressure as well.

Benefits from the use of cover crops have been well documented and even discussed within this publication. Some Pecan South authors who have contributed to this effort are Charles Rohla, Richard Heerema, Lenny Wells, Monte Nesbitt, Mike Brensel, Charlie Graham, and Mallory O’Sullivan. I encourage you to search their articles as they may touch on other factors regarding cover crops and soil health that I am not thinking about here. They may also have more specifics on cover crops’ uses and benefits.

Most of the benefits of cover crops in an orchard system involve protecting the soil from erosion, providing better access to the pecans on the ground (like in clay soil with large cracking), or maintaining orchard access for harvest because of firmer ground. The suppression of other weed pressure is a great benefit too. But probably the top three most important benefits, especially for western producers, are 1) the cost savings on labor and fuel incurred from tillage and herbicide applications; 2) increase in soil organic matter; and 3) improvement of water infiltration and water holding capacity of our arid desert soils.

Just think about how hot those arid, bare soils get in the summer. If nothing else, think about the research showing how extreme soil temperatures actually kill and decrease beneficial soil microbes. Now think too about where most of the feeder roots are located within our pecan orchards (they’re just beneath the surface) and the mycorrhizal fungus synergistic relationship, and how that is sensitive to these extremes. Cover crops will offer an optimal soil environment at the depth where all this soil biome activity occurs and at the pecan trees’ critical root-soil interface exchange points.

I recall a comment made to me by a soil scientist. They stated that just the act of transitioning to no-till operations alone would increase soil organic matter and reduce carbon losses. One important goal as land stewards is to capture and sequester carbon, not release it. Remember, every disruption of the soil, even a shovel scoop, releases carbon back into the atmosphere.

Increasing soil organic matter increases soil stability. It directly and positively influences soil aggregates and feeds the soil decomposers. Soil organic matter is a food source for soil decomposers, and their chemical by-products hold soil aggregates together. Allowing the native grass and weed species (known as “resident vegetation”) to grow between the tree rows will improve soil organic matter.

I also recall a study that found that every 1 percent gain in soil organic matter results in as much as 25,000 gallons of available soil water per acre. This increase in water holding capacity is why I say that the western region would benefit the most by using cover crops.

You could probably think of other benefits than what is here, especially in terms of the benefits in relation to your pecan trees’ age. The advantages will be a little different for young, new transplants than for mature, bearing trees.

The overall benefits and returns on this investment directly relate to soil health, such as aggregation, microbial activity, tilth, nutrient availability, water holding capacity, and reduced compaction. So, there’s a lot here on the advantages and uses “for” utilizing cover crops in agriculture production. Still, even as you read through these, your mind probably drifted to some drawbacks and challenges as well.

The Challenges With Cover Crops

The first challenge is water availability, at least for the West. This is a limiting factor indeed for most western pecan producers. However, in the last 5 years, more research has been done on the native grasses that survive on little precipitation in the arid desert and their uses as cover crops. Though if an operation is going to incur the expense of purchasing a cover crop seed blend, they certainly will care for it as an intentional crop by giving it the water required to grow optimally. So, if there are drilled or broadcast seed between tree rows, irrigation water will need to reach the tree middles—something to consider, especially depending on your trees’ size and age.

Drilled seeds are planted in the orchard floor during dormancy in order to start establishing a cover crop. (Photo from FICO)

Another challenge that cover crops present is added time and management. Although you reduce herbicide application and tillage when you plant a cover crop, you replace those tasks with an intentional crop that requires management. After all, even though equipment passes through the orchard are reduced, this crop still must be mowed. Cover crops may also increase the spring and fall workload—yet another challenge.

Weed potential creates a third challenge. Some of you may realize that the cover crop, depending on the species, could become a weed in itself. A “weed” is just an unwanted flower. Or if the timing of seeding and growing the cover were slightly disrupted or off, native weed vegetation could out-compete and negate your purposeful seeding of the cover crop. But, as land stewards, you know and watch seasonal shifts of climate events and could plan around this as best as possible, even as much as simply having the seed and equipment lined up and ready.

Some locations, especially in the high country, may also face the challenge of increased frost threat. A late winter cover crop reduces the soil’s heat absorption during the day, which potentially increases the frost damage risk after leaf-out in spring. However, management of the cover can reduce this. For instance, mowing the cover down allows for more sun exposure to the soil surface during the growing season.

Cover crops could also impact pruning timing. If the cover establishes itself significantly, depending on how winter favors it, shredding and removing prunings left on the orchard floor could be difficult or even take extra labor and effort. In this regard, perhaps be mindful of the sequence of events around pruning and hedging, and in having crews ready and in rotation quickly enough to get these prunings out and shredded as quickly as possible.

A few other challenges may present themselves depending on the specific orchard’s location and farming strategies. A couple of other challenges that come to mind are the potential for the cover to become a habitat for not just beneficial but possibly harmful insects. Or another challenge—if the orchard is already experiencing high populations of pocket gophers, a cover crop would offer them greater food source and make the population difficult to manage since it could hide their mounds.

Like pecan trees, cover crops also require management. Mowing is one task that may be added to farmers’ to-do lists after planting cover crops. (Photo from FICO)

These are just some challenges to consider. After all, it is part of the process of designing your specific cover crop regime and how to handle the potential challenges that may present themselves in regard to your farm’s existing ecosystem. But now, let’s examine some cover crop options for western producers.

Types and Timing

First, think of the cover crop species in terms of an annual or perennial cover. Many annual cover crops are planted in the fall or late winter months (January/February is a good time for seeding here in Southeast Arizona), whereas farmers plant perennial cover crops after soil temperatures are warm enough to favor seed germination. Many available resources list the best seeding timing of specific species and the types of cover crops.

Some of the most common annual cover crops in the West are annual ryegrass, cereals, cereal rye, clovers, field pea, medics, mustard crops (brassicas), and vetches. Farmers typically allow these types to flower and broadcast their own seed for reseeding potential. Remember though, some of these are nitrogen-fixing species that capture nitrogen and store it in their root nodules. Some research has shown that allowing them to flower causes some of this stored nitrogen to go to seed production. If the goal is to capture as much nitrogen as possible and make it available for the cash crop, perhaps plan to mow these types before they seed. Side note: if you’re dealing with soil compaction, the radishes should definitely not be overlooked.

Some of the most common perennial cover crops include fescues, Indian ricegrass, meadow barley, perennial ryegrass or wheatgrass, white clover, and wildflower and forb mixes. One study performed here in Arizona by the NRCS Tucson Plant Materials Center (PMC) investigated the use of several native grass species in pecan orchard systems. Specifically, they experimented with six treatments of ‘Plains’ buffalograss, ‘Hachita’ blue grama, Westwater germplasm scratchgrass, and Moapa germplasm scratchgrass planted in an orchard in Willcox, Arizona. By the month of September, the grama and buffalo grass had the most promising performance even with other weed competition.

When it comes to deciding between various cover crops, planting a blend of these different types, if the financial resources are available, will undoubtedly produce the best results in terms of benefits observed.

Final Thoughts and Resources

As a horticulturist and arborist, I am always learning. In my travels around here in the West and through my observations of various cropping systems, I truly think we could use more cover crops. I challenge you to try it in your orchard, even if it’s just a little piece of the farm at first. And I encourage you to challenge me too. I am always welcome to more learning opportunities.

If you’re a western producer and this article has piqued your interest in implementing cover crops in your operation, your highest priority should be to start with a list of pros and cons specific to your farm management goals, calendar, and micro-ecosystem. Once you’ve done that, add a list of four or five objectives and goals for utilizing cover crops. One example of this could be that the farm wants to increase soil organic matter by 1 percent. Third, decide how the farm will monitor and track progress so that you can determine when your operation achieves these goals. For instance, if your farm wants to use the cover crop to cycle nutrients and reduce nitrogen inputs and losses, then figure out how to monitor this goal so management can observe the benefits and cost return?

Lastly, I recommend seeking out your local Land Grant University Extension Agent and NRCS office if you want to incorporate cover crops in your operation. The extension service can suggest cover crops suited for your area, and the NRCS has a program in place to help producers get started with incorporating cover crops. The program is called the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), pronounced “equip.”

The NRCS also published results of the Southwest cover crop experiment, initiated in 2015. The report gives some excellent details on many cover crop species evaluated in western arid land. It can prove a good resource when selecting cover crops to implement in your western operation.

For readers in some of the central and eastern pecan production regions, or even others for that matter, the USDA-NRCS Plant Materials Program provides the national results and evaluation of cover crop performance and adaptation around the country on its website here.

Other Valuable Sources:

Noble Research Institute – Cover Crops.

Evaluation of Cool Season Cover Crops in Southern Arizona – Final Report – Tucson Plant Materials Center.

USDA-NRCS Common Species & Cover Crop Properties.

GreenCover Seed–Even a SmartMix Calculator to help