Family Trees: Looking back, Going forward

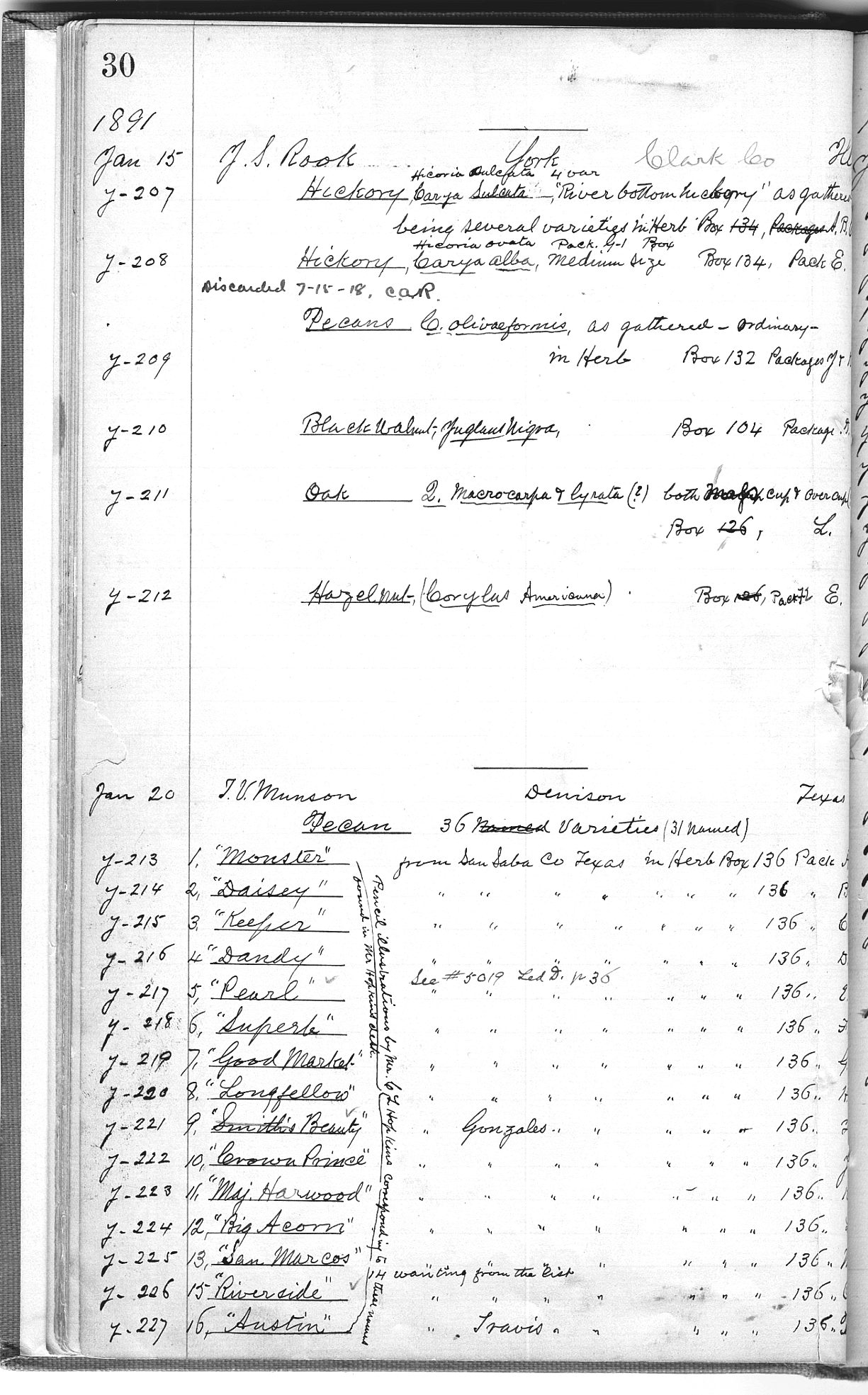

Figure 1: USDA Logbook entry of pecan samples from T.V. Munson, received Jan. 20, 1891.

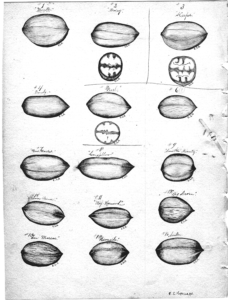

Figure 2: C.L. Hopkins’ drawings of the T.V. Munson samples. ‘Longfellow’ was number 8 in the page 30 list and sample Y-220 Jan. 20, 1891.

The following stories are the records of tens of thousands of trees now growing in orchards across Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. These are the stories of our pecan growing families, stretching from the pioneers who laid the foundations of the U.S. pecan industry to the current generations of growers who are marketing nuts in 2019. And more specifically, these are the stories of individual trees we maintain in the USDA ARS National Collection of Genetic Resources for Pecans and Hickories (NCGR-Carya).

Research teams are actively improving the tools we need to accurately identify trees and trace their heritage. These tools will help commercial nurseries ensure that the trees sold are truly identified and will help us select the next generation of regionally adapted cultivars and rootstocks. All of the information presented here has been published in research papers that most pecan growers will not read. This information and these pictures are stored in files that are the genealogical records of the pecan industry. Those files are being woven into databases that must be and will be accessible and useful to growers as well as researchers. Accuracy requires documentation, so references are provided. Hopefully, the stories in this article will help establish conversations about these developing tools, the developing database, and the existing collections that will help unite our family as we look back and move forward in the future.

Longfellow

Nut size and shape have always been used to select and distinguish valuable trees. In the 1890s, pecan growers from all around the United States sent nuts to the USDA Plant Introduction Station in Washington, D.C. NCGR-Carya has old logbooks recording where many nut samples came from. The first samples of ‘Longfellow’ were sent to USDA in 1891 from T. V. Munson, a world-famous Texas horticulturist who is credited with saving the French grape industry by sending phylloxera resistant grapes for use as rootstocks. Munson collected pecan samples in San Saba, Texas (page 30 of Logbook 1)(Figure 1) as well as in Gonzales and Travis County. He may have been working in cooperation with E.E. Risien, one of the fathers of the pecan industry (Crane et al., 1937; Wolfe, 1946), but we do not have records of that. Pencil illustrations of the Munson nut samples were drawn by C. L. Hopkins (Figure 2), and highlight the value of modern photographic methods, but also the dedication and accuracy of the Plant Introduction Station staff.

Figure 3: ‘Longfellow’ nut sample Y-220 from T.V. Munson collected in San Saba, Texas and received on Jan. 20, 1891. This sample is maintained in the McKay Nut Collection at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C.

I was surprised to find the Munson pecan samples stored in jars as part of the McKay Nut Collection, USDA ARS National Arboretum (USNA), Washington D.C. I photographed the entire nut collection in 2004 (Figure 3).

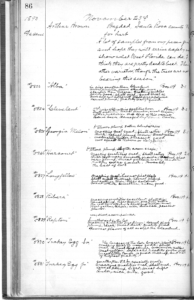

The next samples of nuts bearing the name ‘Longfellow’ were sent by Arthur Brown from his orchard in Bagdad, Florida in 1893 (#5827, page 86 of Logbook 1)(Figure 4). Brown had purchased that orchard in 1883 from John W. Hunt. Hunt established the planting using selected seed that his slave collected from pecan trees growing along a river in either Texas or Mexico during the Mexican-American War (1846-48) (Blackmon, 1929). Noteworthy seedling selections from Brown’s orchard resulted in ‘Elliott’ and ‘Curtis,’ but that is another story for another time. The important relation to this story is that the nuts that Brown sent under the name ‘Longfellow’ were grown in Florida and may be a different genotype than the nuts sent by Munson from Texas. The pecan samples Brown sent are also present in the McKay Nut Collection at USNA (Figure 5).

Figure 4: USDA Logbook entry of pecan samples from Arthur Brown, Bagdad, Florida, received on Nov. 23, 1893.

Samples of nuts bearing the name ‘Longfellow’ were sent to USDA by E.E. Risien in 1907 (#39928)(Figure 6). We do not have a logbook showing the entry of these samples, but nuts in the McKay Nut Collection are well-documented.

‘Longfellow’ was listed as one of the cultivars offered for sale in the 1903-1904 Price List of E.E. Risien’s West Texas Pecan Nursery. In his 1908 catalog, Risien included a labeled picture of nuts from cultivars offered for sale, including ‘Longfellow’ and a sample named ‘Riverside’ (Figure 7).

Tommy Thompson and I obtained ‘Longfellow’ graftwood in 1993 from the Lucas Orchard, Brownwood, TX (Lucas, Row 11, tree 29). H. G. Lucas of Brownwood, Texas was the first President of the Texas Pecan Growers Association. What we call the Lucas Orchard was planted as the Swinden Orchard and described on the nearby Texas Historical Marker:

“Pioneer in the improved-pecan industry of Texas; founded 1888 by English-born F. A. Swinden. He began cultivating the trees in this area, where they grow wild on Pecan Bayou, and developed the large “Swinden Pecan” as well. Here, on 400 acres, he planted his orchard, which by 1894 had 11,000 trees from one to six years old. He started the first irrigation project in region by building a dam across the bayou. In 1919, H.G. Lucas and partner, Wm. Capps, acquired the orchard. Lucas operated it more than 40 years and shipped pecans to markets all over the world. (1968)”

Figure 7: Labeled pecan nut samples from E. E. Risien’s West Texas Pecan Nursery Catalog (Risien, 1908).

I grafted the ‘Longfellow’ wood from the well-documented Lucas orchard into the pecan cultivar collections of the NCGR-Carya at CSV 13-4 in 1993 (Figure 8). Lynn Johnson used wood from CSV 13-4 to graft an Apache seedling rootstock into the Brownwood collections at BWV 2-30 on 17 Apr 2003 (Figure 9), and wood from that tree to graft BWV 3-17 on 27Apr2005. Nut shape of our ‘Longfellow’ samples is oblong narrowing to the base, with an acuminate apex. That is generally consistent with the 1891 samples collected by Munson from San Saba (Figure 1), drawn by Hopkins (Figure 2) and photographed from the McKay Nut Collection (Figure 3). It is very consistent with the photograph of Longfellow from Risien’s 1908 catalog (Figure 7). As we continue to accumulate verification information on particular tree inventories, moving graftwood from those inventories to other labeled trees transfers the confidence of previous verifications. As new information is associated with an inventory, updating the records in a computer database should help all of us who use those records stay current.

Western

‘Western Schley’ was the name originally given to a pecan cultivar introduced by E.E. Risien in his 1916 Catalog (Risien, 1916). Since ‘Schley’ (Taylor, 1905) is an important pecan that originated in the southeastern United States, the name was a source of confusion and is commonly shortened to ‘Western’.

The first inventories of ‘Western’ in our collection were obtained as grafted trees from Wolfe’s Pecan Nursery and planted as a major component of the first orchards at the USDA Brownwood Pecan Station in 1932. The tree in the Brownwood Main Orchard at BRW 7-19 was the inventory used for isozyme profiling (Marquard et al., 1995), and was the source tree for graftwood to establish the College Station inventory at CSV 21-22 when it was grafted April 11, 2001 (Figure 10).

‘Western’ is the backbone of the western pecan industry. Thompson (1990) collated estimates of pecan cultivar acreage from across the national pecan industry and reported that only ‘Stuart’ (then with 47,703 hectares) had more acreage than ‘Western’ (then with 31,848 hectares). Details of the cultivar’s history, characteristics and performance were summarized in general by Thompson and Young (1985) and in detail by Sparks (1995), although current origination information modifies those accounts.

Many publications (Crane et al., 1937; Thompson and Young, 1985; Sparks, 1995, Texas Forest Service) have suggested that ‘Western’ originated from nuts that Risien planted of the ‘San Saba’ pecan. That is not accurate. The value of appropriate molecular genetic markers is that these markers can objectively confirm the cultivar’s identity and, at times, its parents. The first reliable markers used in the pecan collections were isozymes (Marquard et al., 1995). ‘Western’ could not have grown from a ‘San Saba’ nut, because the markers found in some molecular sites in ‘Western’ are not present in ‘San Saba.’

Riverside

The origin story of ‘Riverside’ is more complicated than those of ‘Longfellow’ and ‘Western.’ In order to recognize the true ‘Riverside,’ we will need to disqualify the first sample bearing that name (Figures 1, 2, 7 and 11) by using nut measurements. We can qualify other samples as true ‘Riverside’ based on propagation records. Then we will tie the historical records of ‘Riverside’ with molecular genetics to understand its origin.

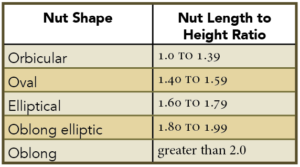

At the USDA ARS Pecan Breeding & Genetics Program, five individual nuts for each sample are weighed and measured. Measurements are made of nut length, width, and height. Nut width is measured with calipers touching the sutures, and nut height is measured perpendicular to width. Buoyancy is determined by weighing the nut under water. Nut volume is calculated by adding buoyancy and nut weight. Nut density is calculated by dividing nut weight by nut volume. The ratio of nut length to height provides the basis for describing nut shape:

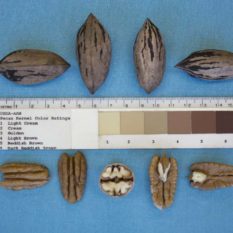

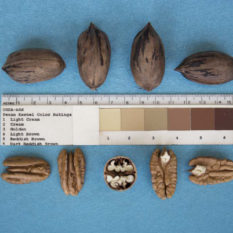

Nut samples are arranged to standard configurations on a light blue background and photographed with a label showing the Orchard, Row, and Tree, with the year, along with and a size and color scale. Numerical nut quality data for that tree’s nut sample in that year can be linked to its image. By having many images of the same tree of the same cultivar over different years, variation in nut size and shape can be seen and studied. When I describe a nut as “oval” versus “elliptic,” I am referring to categories based on nut length to height ratios.

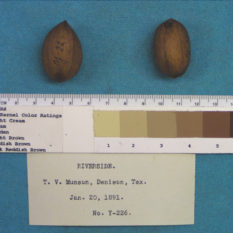

A nut sample named ‘Riverside’ was part of the lot of nuts T.V. Munson collected in Gonzales, Texas and sent to USDA in 1891 (#15, Y-226, ‘Riverside’, Figure 1)(#15, ‘Riverside’, Figure 7)(Y-226, ‘Riverside’, Figure 11). A cultivar named ‘Riverside’ was also being offered for sale in Risien’s West Texas Pecan Nursery in 1908 (Figure 7). These samples are all elliptic in shape with length to height ratios between 1.65 and 1.76. It is possible that in 1908 Risien was propagating the same tree that Munson sampled in 1891. He was also propagating a sample named ‘San Marcos,’ which Munson also sampled from Gonzales in 1891. Hopkins’ drawing of ‘San Marcos’ shows an elliptic nut (1.61), while Risien’s picture is of an oval nut (1.42), but single nut measurements are variable.

The cultivar that we know as ‘Riverside’ is a seedling selection of unknown date attributed to H.H. Cockrell and “thought to be a cross made by E.E. Risien” (Thompson and Young, 1985, pp. 79). The earliest reference to the cultivar as rootstock was by Ross Wolfe (1946) who referred to it as a product of Risien’s breeding efforts that “gives promise of being an extra good variety for nursery seedling understock.” ‘Riverside’ was used as a seedstock at Cockrell’s Riverside Nursery and was the preferred rootstock of D.F. Stahmann, originator of Stahmann Farms (Cockrell and Doak, 1984). Records at NCGR-Carya note the involvement of George Robertson, on whose land at Big Valley, Mills County, the original tree grew.

The first inventory of ‘Riverside’ at the USDA Pecan Breeding Program was received in 1967 from Cockrell’s Riverside Nursery and was grafted at BRW 70-14, from which the tree at BRW 127.5-39 was established in 1971. That inventory was the source of tissue used in isozyme research (Marquard et al., 1995). Additional ‘Riverside’ graftwood was obtained from Cockrell’s Riverside Nursery in 1993 and was used to establish the tree at CSV 3-1 (Figure 12). That tree was the source of tissue for genotyping by sequencing (GBS) research (Bentley et al., 2019)(Figure 12). Nuts of our ‘Riverside’ inventories are oblong elliptic with an acute apex and rounded base. Nuts are longer and have a more pointed apex than the early samples from Gonzales, sampled in 1891 by Munson (Figure 11) or propagated by Risien in 1908 (Figure 7). Since our trees were established from graftwood obtained directly from the originating nursery, they are trustworthy.

As the list of cultivars grows, it helps to have nut samples of known cultivars against which to compare unknown samples. The USDA Pecan Breeding Program maintains a “Nut Library” with nut samples (or vouchers) collected from trees of known cultivars. In order to know the exact tree that a sample came from, the Orchard, Row and Tree numbers are recorded on the vouchers. In the mid-1990s, we began photographing nut samples using a standard system of arranging the nuts to show both the suture side and upper surface, with size and color scales included. It is much faster to retrieve the digital image of nut samples on a computer than it is to retrieve a physical voucher from the Nut Library. Nut images were made internationally available in the late 1990s in the “Pecan Cultivar Index” of the program’s website, along with general information about the historical origin of the cultivar.

When all we have to go on is the cultivar name and nut shape, it is hard to be certain of genetic identity. It is not as important to be certain about whether Munson’s ‘Longfellow’ was the same as Arthur Brown’s as it is to know that living inventories of ‘Longfellow’ in NCGR-Carya connect to Risien’s samples. Although the first cultivar propagated by Risien as ‘Riverside’ is not consistent with the modern cultivar, the genotype specifically selected for use as a rootstock was obtained from its originator, Cockrell’s Riverside Nursery, and is linked to Risien by the testimony of knowledgeable contemporaries (Wolfe, 1946) and by molecular genetic evidence. As in all genealogical research, it is valuable to be able to prove that both parents are older than their progeny. Records of the origin of ‘Longfellow’ meet that condition for both ‘Western’ and the true ‘Riverside.’ If the 1891 Gonzales sample of ‘Riverside’ could not be disqualified on the basis of nut morphology, it would raise problems by being contemporary with its parent and found in a distant location.

Management of the diverse collections of NCGR-Carya has necessitated objective methods to identify trees that were more reliable than nut shape. The first reliable markers were isozymes (Marquard et al., 1995) which could confirm tree identity and could disqualify parentage in some instances. Markers found in the parent trees will also be found in the progeny, but common markers are found in many cultivars. Isozymes were valuable in correcting mistaken information on some cultivar origins. For instance, ‘Western’ could not have grown from a ‘San Saba’ nut because the markers found in some molecular sites in ‘Western’ are not present in ‘San Saba.’ In order to trust the molecular profile, you must trust the tree that produced it. We knew we had true ‘Western’ and ‘San Saba’ trees so we trusted the isozyme information to disqualify ‘San Saba’ as a parent, but we did not have enough information to identify the correct parent.

The next markers attempted were called simple sequence repeats (SSRs) or microsatellites. Those 14 nuclear markers have been valuable in verifying identity, confirming parentage and, with the use of only 3 maternally inherited plastid markers, confirming which was the nut parent in a controlled cross (Grauke et al., 2015). Since some markers are characteristic of particular hickory species, hybrids between species can also be detected (Grauke et al., 2015). Plastid markers contributed to understanding regional patterns of diversity, distinguishing southern populations from northern (Grauke et al., 2011). SSR marker profiles were consistent with ‘Longfellow’ being the parent of both ‘Western’ and ‘Riverside’ but were not conclusive. The recent application of genotyping by sequencing (GBS)(Bentley et al, 2019) greatly increases the resolution of genetic relatedness between pecan cultivars and clearly confirmed that ‘Longfellow’ is a parent of both ‘Western’ and ‘Riverside.’ The detailed genetic information provided in this research (Bentley et al., 2019) will help us refine genetic profiling procedures for use by nurseries to certify cultivar identity. Improved resolution of genomic patterns and their relation to tree traits will eventually improve regional selection of both rootstocks and scion.

The short history of the pecan industry, its thorough and well-documented collection of wide-ranging sources of selected cultivars, and the availability of many known crosses between specific parents provide a valuable foundation for the development of marker-assisted selection. Working with a panel of about 100 historic pecan cultivars, Bentley et al. (2019) looks back across that short history and answers many questions. Nolan Bentley is a graduate student working toward his doctorate under Patricia Klein, Ph.D., at Texas A&M University. They are part of a national team of researchers working with pecan in general and within the genetic collections and test systems of the NCGR-Carya and USDA Pecan Breeding Program specifically to improve genetic tools. Currently, we are all working within a USDA Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant, headed by Jennifer Randall, Ph.D., at New Mexico State University (Coordinated Development of Genetic Tools for Pecan). As we look forward, the next generation of researchers will not have the opportunity to personally know the pioneers of this industry, but these records document their contributions. The dominant story woven through these records is that some of the best cultivars and rootstocks in use today are not the product of a government breeding program, but are actually the product of a dynamic industry. By archiving each cultivar’s records of origin, performance, and genetics into an accessible database, we are tying together these stories and scientific findings to living trees in our orchards, and ultimately, creating a resource that will serve the industry for years to come.